Camping out under the stars, far from the numbing light and noise of cities, is where outdoor enthusiasts know cares fade away and the stresses of daily life are released. One topic of debate among the outdoor community, however, is cell phones. I know people who keep them on and charged at all times, and those who leave them behind entirely. I personally always bring mine along, but keep it on silent-mode to prevent any distractions, as I do feel safer knowing I can contact aid. It’s tough to find a campground in modern-day America that is outside the reach of cell towers and satellite service, and some campgrounds I have stayed at recently even have their own WiFi network!

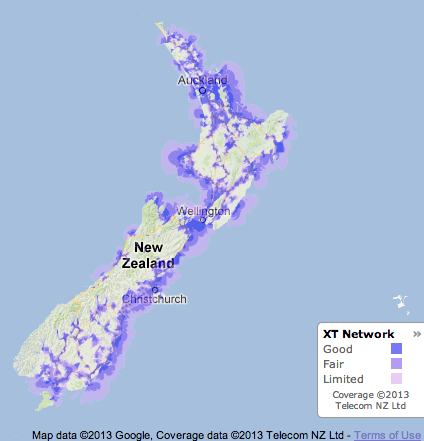

However, this constant connection is not present throughout the majority of New Zealand. Tourists complain about expensive, slow internet even within the nation’s largest cities, and outside the metropolitan regions, cell reception is hard to come by. The main 3 networks, Spark, 2Degrees, and Vodafone, claim to cover over 95% of “the places where Kiwis work and play”, but as 86% of New Zealanders live in cities, this means that barely 50% of the nation’s land area has cell service.

Being cut off from cell networks might be a scary part of my New Zealand adventures. I’m accustomed to having an emergency solution in the palm of my hand, so I’ll need to remember to take extra precautions. Before leaving for a hike or overnight stay in the wilderness, I’ll let someone know where I’m going and when I plan to be back, so they can check on me if I take longer than expected to return. A compass is also a must-bring item when GPS isn’t reliable. As long as I stay safe, perhaps I’ll even appreciate being freed from the tethers of cell networks!